Without any planning, my self-isolation reading introduced me to four strong women. They lived in sixth century Ireland, pre-BC Israel, and 20th century North Carolina and Youngstown Ohio respectively.

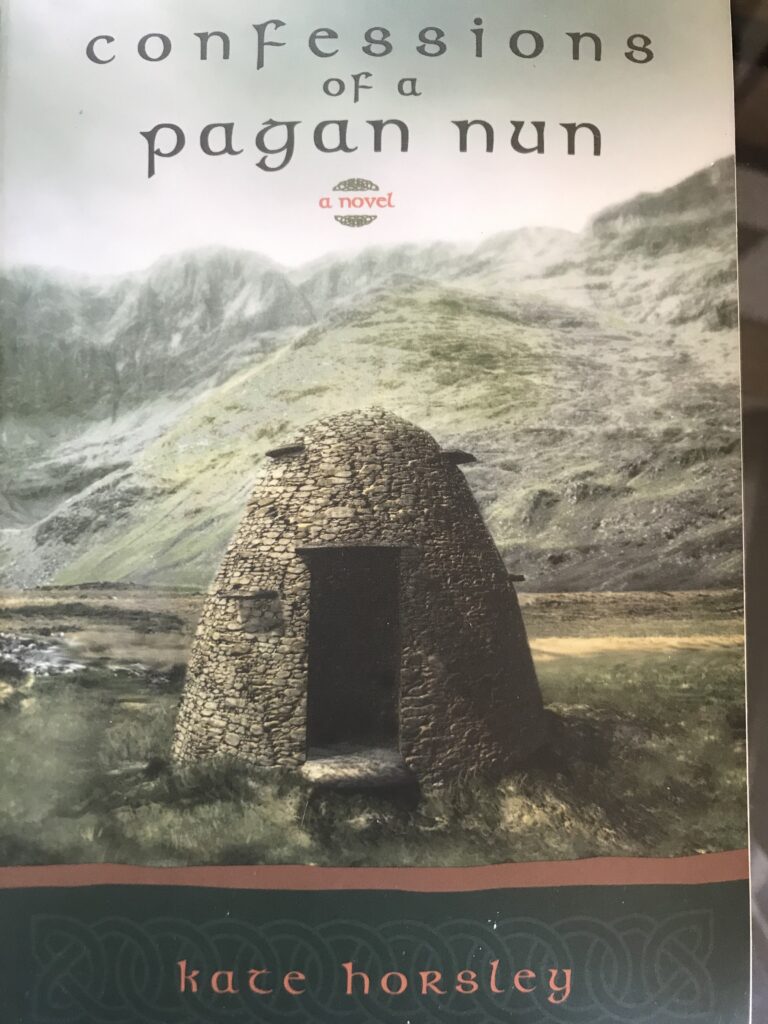

Confessions of a Pagan Nun by Kate Horsley

With a title like that, you know that the story may end badly. This small, powerful novel by Kate Horsley relates in first person the conversion of Gwynneve, a sixth century woman living in Ireland, from a druid to nun.

Gwynneve is raised by a mother who teaches her the powers of the earth, the alchemic qualities of plants for healing, where they grow and when the best time to harvest might be and where the fairies and spirits abide in the forest. As Gwynneve weaves her story, she is already a scribe and translator at the abbey of Saint Brigit over forty years old and with much worldly experience behind her. Prior to her conversion, she had apprenticed herself to the Druid Giannon. They lived together and were lovers. He taught her the practices of the ways which were being purged by the Christian fathers, and their followers, the sisters.

Gwynneve relates her story with literal candor. She observes the world that is changing, the elevation of church over the welfare of the tribes which were dissolving. She witnessed the methodical misogyny of the original sin doctrine (and the conflict of the Pelagians).

Gwynneve who spends her life at the abbey in a small, stone beehive shaped clochan transcribing and unwittingly becomes the victim of a scandal, then accused of heresy, always a convenient church charge.

This is a quiet book yet its reflection on dogmas, spiritual and otherwise carry powerful messages in our contemporary world. Highly recommended.

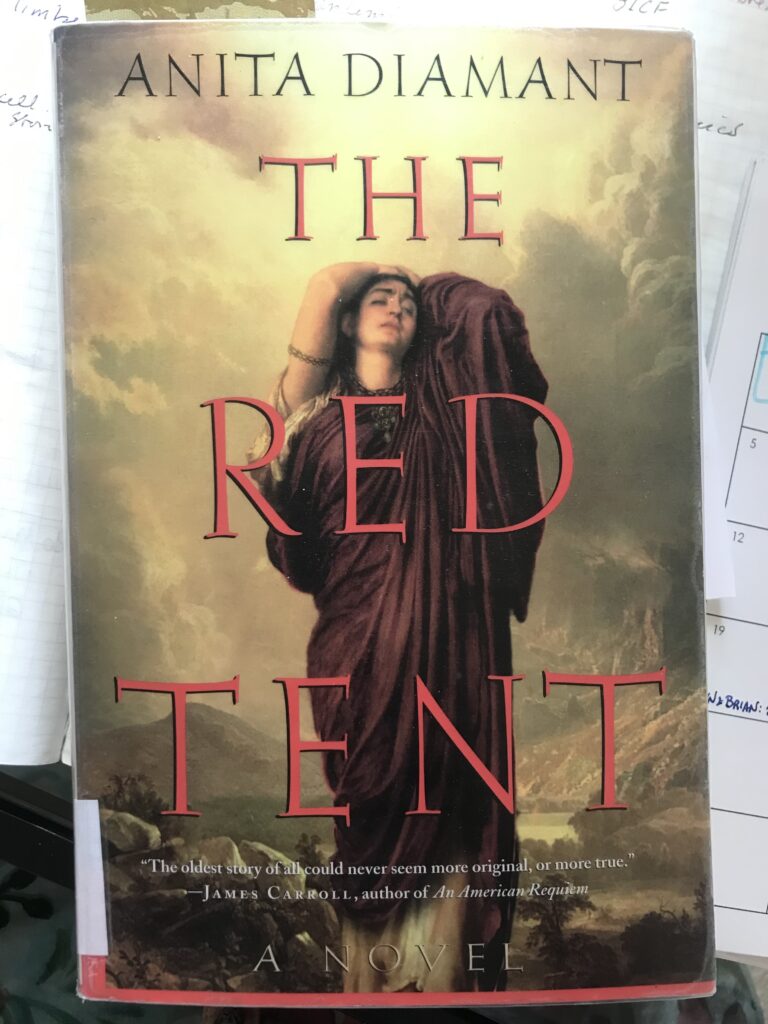

The Red Tent by Anita Diamant

Anita Diamant choses to give voice to Dinah, the daughter of Jacob and Leah as told in the Bible’s book of Genesis, rather than allow the patriarchs tell her story. Although scholars debate the story, the party line is that Dinah was raped and although the erstwhile attacker seemed smitten and wanted to marry her, brothers Simeon and Levi savagely revenged the affair. After all, if women could chose their partners and, God forbid, have passion of their own accord and not the bidding of their husband (or father/brother/male) , the world might end.

Ms. Diamant invites us into a private world where women have a voice among themselves and guard that independence fiercely. Told in Dinah’s own voice, in the desert culture of Abram’s children, men have the last say. Women use guile to get their way, yet they are the healers, the caretakers, the bearers of children.

Dinah tells her story of a period of transition, much like Confessions of a Pagan Nun, when idols were losing acceptance and male oriented dogma was changing old customs.

Without much Biblical knowledge (next to none sad to say) The Red Tent completely engrossed me. Christian orthodoxy spawned from these tales, historic or metaphoric, and “attention must be paid.” Ironically, or perhaps not, the name Dinah was the generic name given to enslaved African women in our country. Sambo being the male counterpart.

Dinah wants her story known, (no spoiler here) and she tells it with grace, clarity and intelligence.

I love the ending as she reflects, “In Egypt, I loved the perfume of the lotus…Egypt loved the lotus because it never dies. … It is the same for people who are loved.” This directly relates to a book that I’m in the middle of reading. More on that later. Isn’t synchronicity wonderful?

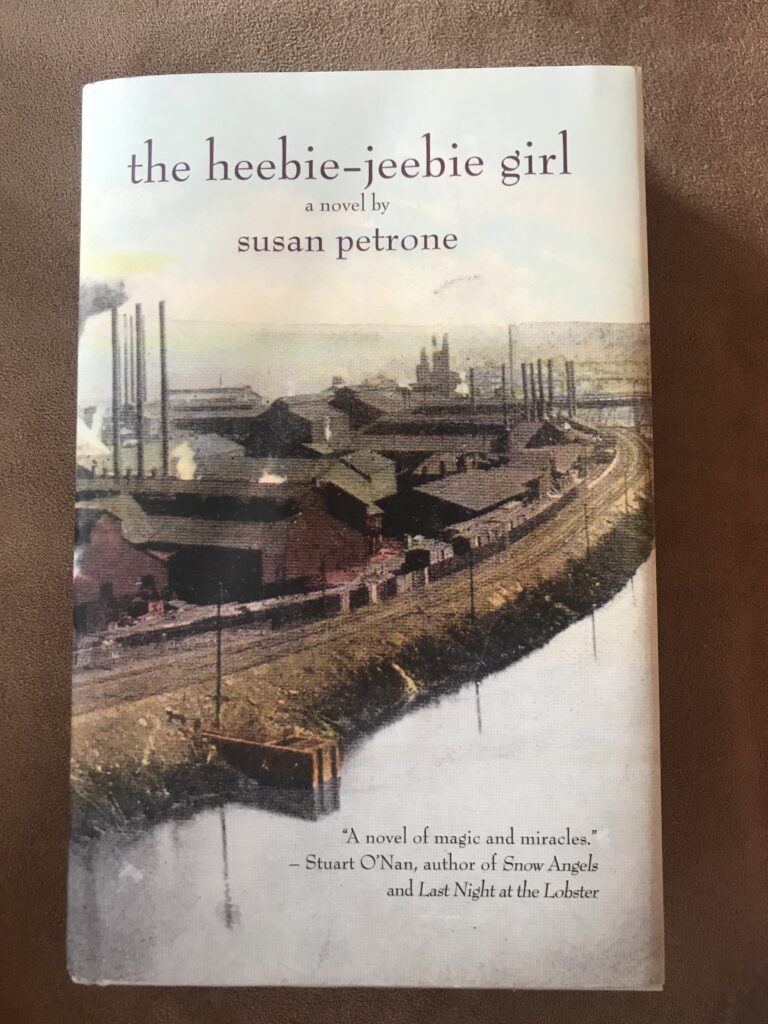

The Heebie-Jeebie Girl by Susan Petrone

There must be something about Rust Belt cities that gets into your bloodstream. Although I haven’t lived in Cleveland for decades, references to billboards that move, cassata cake, and Browns’ fumbles provoke a sentimental “thrum” in my heart.

Susan Petrone’s latest novel, The Heebie-Jeebie Girl isn’t a novel about Cleveland, but its cousin, Youngstown, Ohio. Imaginative and clever (two different skills) she weaves a working class tale with an unlikely heroine, second grader, Hope. It takes courage to use such a protagonist in an adult novel, but Ms. Petrone (full disclosure note can be found here) captures the cadence and contradictions of Hope without any adult patronizing.

Anyone who has lived in a steel town with stacks blowing smoke at all hours, sprawling behemoth factories that housed gigantic blast furnaces, relates to the devastating effects the sudden shutdowns in the seventies had on thriving cities. This is a tale of those days with magical realism thrown in for good measure. (Another disclosure, my paternal grandfather had several patents on blast furnaces which he installed in Birmingham, Alabama. )

The Heebie-Jeebie Girl captures the homes (my maternal grandparents in South Euclid) exactly. The spotless basements. Yes, basements kept tidy as only those who knew the privilege of owning a home could keep. Losing a home to “progress” (my paternal grandparents lost their home in Lakewood by public domain to make way for I-90 heading west). It reflects the pride of these industrial workers who were robbed of an honest living, the beginning of off-shore trade agreements that lined the pockets of few and left a residue of broken dreams, the effects of which we are feeling in today’s cultural and political turmoil.

Susan Petrone has a breezy writing style that hits you with a velvet hammer of intelligence. I like it.

Check out this novel and her others as well. I won’t spoil the surprise voice in Heebie-Jeebie, but it delivers a spot on description of young men and sex.

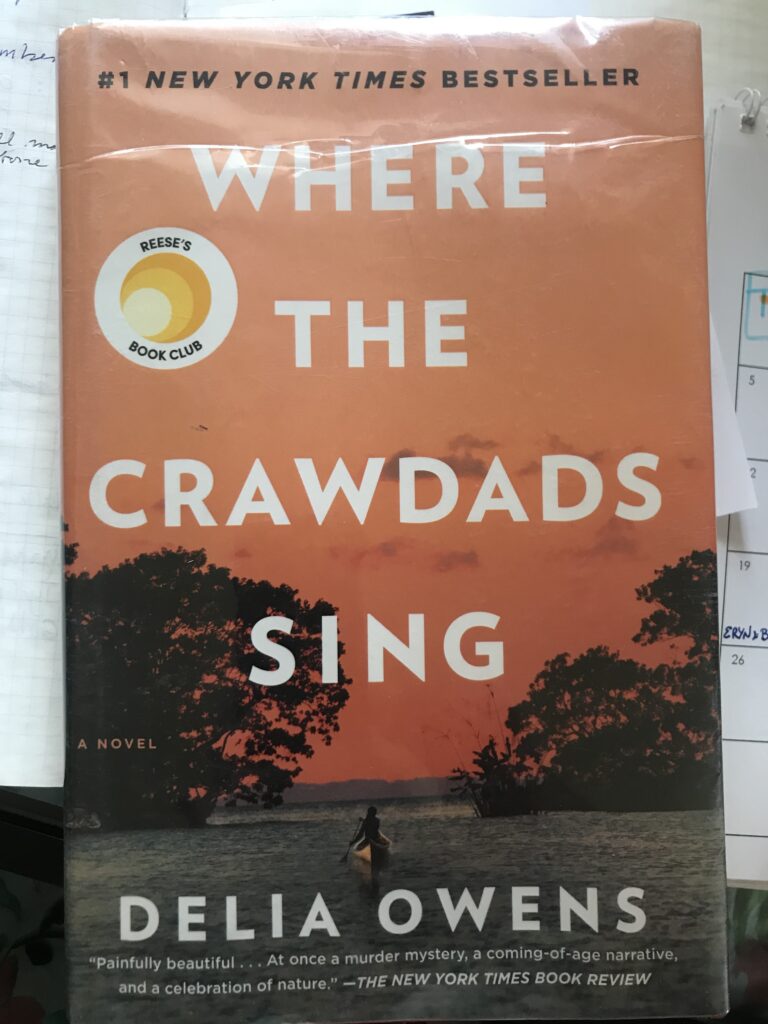

Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens

As a zoologist, Delia Owens specializes in observation. Lucky for us because she is able to paint a portrait of complicated backwaters, tidal marshes and channels, slip streams, and sand bars that serve at the whim of the Atlantic Ocean’s legendary Outer Banks. Add to the canvas the diverse wildlife that inhabits the shoals, muddy tidewaters, trees, grasses, sandy banks and the people who inhabit the land. I remember spending some time camping on Ocracoke Island in Cape Hatteras and the locals speak with a unique accent that suggests generations of isolation. A somewhat secret society that choses to be independent and marching to the tune of their own drummers.

Kya is the youngest born into a family of an ill-fated marriage, alcoholic husband/father suffering from shame and World War II PTSD. Her abused mother leaves, followed by four other siblings leaving Kya, seven years old with her father. She is intelligent and sent to school but as children are merciless and cruel and teachers sometimes clueless, she never returns. Her life is overflowing with despair without adding the daily torture of school to the mix.

Resourceful, she forges a tentative bond with her father that waxes and wanes with his binges. Finally, he too disappears and she, at age ten, sets out to support herself by bartering harvested mussels and smoked fish. She becomes known as the Marsh Girl.

Ms. Owens adds a murder to the mix and as the book unfolds in flashbacks, we watch, and care for Kya as she learns to read, makes small but important human connections and emerges from adolescence into womanhood. Kya is sustained by nature and its rhythms but her human longings, the glimpses of relationships lead her into the world of passion with disastrous results.

In our time of isolation, the nurturing presence of life outside, the creatures that adjust to seasonal cycles, the dependability of the sun’s arrival, the moon’s playful presence in the night sky, the song birds, the survivor’s who live by the tides arrivals and departures, the minutiae of invisible organisms giving rise to robust environments supporting larger players, all these daily miracles can support us as they did Kya, the Marsh Girl.