Sometimes without trying you pick up two books that have synchronicity. I did that last year with The Overstory and Barkskins. This year, I started out with A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles. it’s a prison story. An unlikely prison and unlikely prisoner. Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, condemned to spend the rest of his days in Moscow’s Hotel Metropol. Not hardship duty you might think given the description of his lavish rooms overlooking the Bolshoi Theatre, his balcony and furniture inherited from his distinguished, wealthy family. The Party took care of that as he is unceremoniously banished to a small servant room on the top floor with no balcony. (And no elevator.)

I can relate to this room because once upon a time, I stayed at Villa d’Este in Northern Italy. This was more than forty years ago. The elegance of the morning room where breakfast was served overlooking Lake Como (always famous but now more famous by the residence of George Clooney and his family) stunned me but even more so when the enormous windows quietly lowered into the ground making the room al fresco. For some reason I either wanted to stay longer and they had no room, or I ran out of money and had no place to go. I can’t remember. But what I do remember is that they allowed me to extend my stay one night in the servants’ quarters on the top floor. Since people in the seventies did not travel with valets and maids anymore, it was empty. A small casement window with a deep sill on the outside was the perfect vantage point for a young girl / woman really, to sit on in the evening overlooking the beautiful people enjoying aperitifs and each other.

Although I was in the twenties, I say “girl” because at Villa d’Este, my attempts in fashion and elegance were diminished by the gracious haute couture, beauty, great haircuts and the perfect shade of lipstick by European aristocrats who had had centuries of practice. That night I sat outside the window high above the terrace and watched famed Formula One driver, Niki Lauda, enjoying his evening surrounded by gorgeous women. The next day I left for an ashram in India.

In the case of Count Rostov, he discovered a secret room hidden behind a panel in his closet. This is always convenient and something to keep in mind if you are so imprisoned. So his quarters were enlarged and another convenience was the gold coins hidden in a desk leg dating from Catherine the Great, hoarded by relatives who saw the future of aristocracy in Russia and hedged their bets.

From 21 June 1922 to 21 June 1954, the Count tells his own story (in a voice channeling Cole Porter) about living at the Metropol. He becomes a waiter there. He takes a lover, adopts a daughter, observes the changes in society under a smile-less Communist party. Throughout his imprisonment, he maintains his dignity and patrician arrogance. But nicely. You grow fond of him. He becomes subversive. He longs to take a walk outside. And so he does, but you must read the story to find out just how Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov makes his grand escape.

Another prison, a not so good escape. This is the subject of Iris Murdoch’s, The Black Prince. If you haven’t read Iris Murdoch, please DO! This novel, also in an aristocratic first person voice of author Bradley Pearson, by his own account a talented, but under acclaimed writer of literary substance. He is a mentor to author, tainted because of his abominably commercial success, Arnold Baffin. Similar to A Gentleman in Moscow, the novel takes place in relatively confined (mental and physical) spaces. At least it feels confined. Mr. Pearson is trying to get away to write the novel that will set the publishing world on fire. Instead his heart is set on fire when he begins to tutor Arnold Baffin’s spoiled twentyish daughter, Julian. The fun begins because as Pearson relates, Baffin’s wife Rachel is in love with him as well. Not really as well since he is not sure Julian returns his ardor. Their ages factor in, as he is late fifties, although he professes to Julian a much younger age. Then there is Pearson’s ex-wife, recently returned as a rich widow from America (don’t all widows return from America rich?). She is looking to reconnect as well. Does this sound like a Tom Stoppard play with many doors slamming and characters running in and out with narrow misses? It is comic to be sure but as belies Ms. Murdoch’s work, there is a current of deep humanity searching for meaning. There is Plato and Shakespeare (Ms. Murdoch was a highly respected philosopher). As we are fully immersed in Pearson’s besotted love galloping toward a climax (pun intended) all of a sudden, things change, like life. Perspectives are altered, and the world as we knew it according to Pearson is shattered. What ARE those shadows in the cave?

As Pearson points out, “…the problem remains unclarified because no philosopher and hardly any novelist has ever managed to explain what that weird stuff, human consciousness, is really made of.”

Murdoch is a stealth writer. She can develop complicated plots filled with silliness, pratfalls and humans musing on the mundane, and then she leaves you really about the complexities of human existence and the question of what is reality?

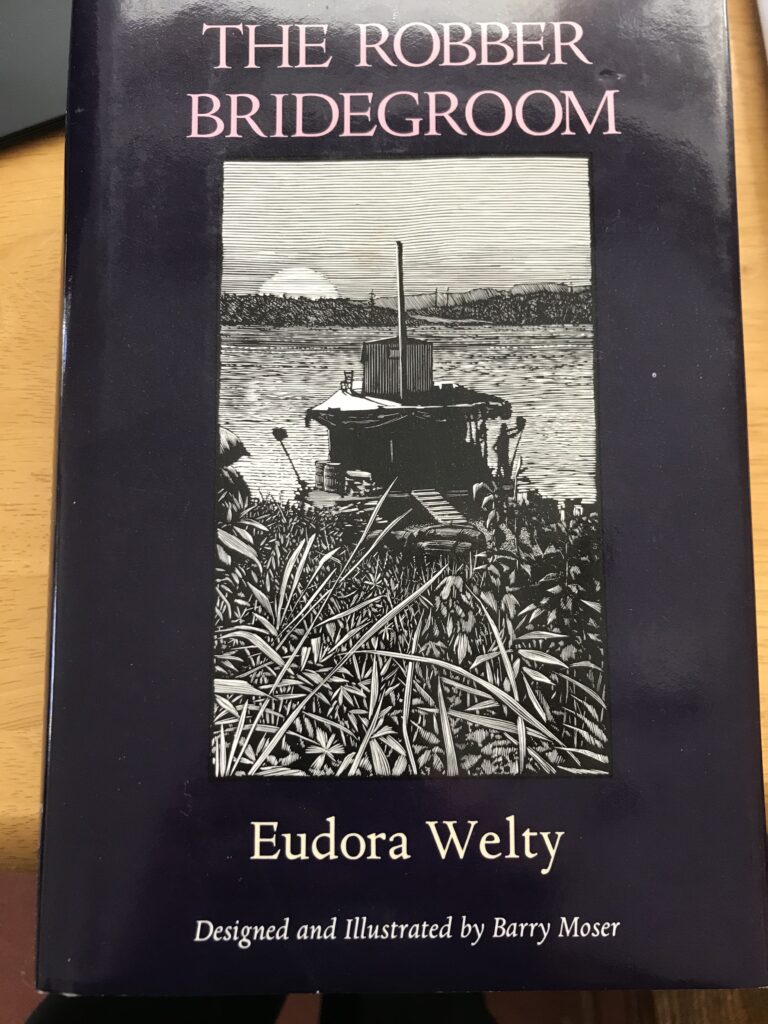

Eudora Welty lived a quiet life in Jackson Mississippi. The literary life she inhabited and created for her readers is rich with characters so flawed, vulnerable, arrogant and anguished they are hard to forget. She writes with a tenderness that we would all like for ourselves, as a consideration. She understands greed, murder, rape and guile.

All these ingredients factor into the strange tale of A Robber Bridegroom, published in 1942, and dedicated to another southern writer, Katherine Anne Porter. At once a fairy tale, a sly social commentary on the American Dream, treatment of Native Americans, women and the hardscrabble life of poor people, The Robber Bridegroom takes us on a fantastical journey of unforgettable characters: the wicked stepmother (I said it was a fairy tale) Salome, Goat, Little Harp, and of course, the beautiful Rosamond and her robber bridegroom Jamie Lockhart.

Miss Welty writes of kidnapping, rape and murder with disturbing aplomb. There is some, but not full, justice in the end. This is a strange, surreal novella best read multiple times. The prose is deceptive, like the swamps and forests the characters inhabit. The humor (imagine a tense fight for one’s life with a willow tree) belies a seriousness and longing that clings to the reader long after she’s finished, like fogs that cause us to get lost in the woods.

My edition was artfully designed and illustrated with exquisite woodcuts by Barry Moser.